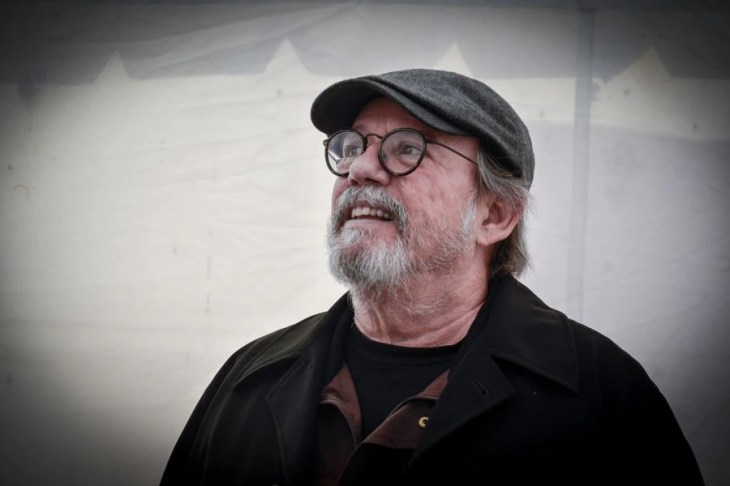

Cuban singer-songwriter Silvio is set to return to Chile to perform later this year. In an interview by Culto recently published in LaTercera in Chile and CubaDebate in Cuba, Silvio talks about his ties with the Chilean people and the current situation in Cuba

“I didn’t think twice.” Silvio Rodríguez (78) remembers clearly and in detail his reaction when he was offered to come to Chile on March 31, 1990: that day, he offered a massive concert to 80 thousand people at the National Stadium in Santiago, not only at the dawn of local mega-events, but also at the dawn of the return of democracy, when his name and his music could already be heard freely, without the suspicious gaze of the military who had banned his songs in the days of dictatorship. It was one of the most memorable mass gatherings of the early part of the 90s in the country.

“We had been ‘clandestine’ in Chile for 18 years. Some of them bought our records in Spain, and replaced the covers. Many Chileans told us that was also done with cassettes. Suddenly came the political change and the possibility of traveling to Chile. I said yes immediately,” the Cuban singer-songwriter deepens, in an email conversation with Culto [column at LaTercera], the way he has chosen to dialogue with the press for decades.

Then he resumes: “Then, I was aware of the mountain of work that it would mean to prepare a concert for that date. It was February and the Havana Jazz Festival was about to begin. Chucho Valdés was almost the sponsor of that event, but when I invited him to come with Irakere (to Santiago de Chile) he didn’t think twice about it either. We started rehearsing right away, in a small nightclub in the basement of the National Theater. In about three weeks of work we put together almost 4 hours of concert. Chucho did all the orchestrations, transcribed the songs I was doing with Afrocuba – who had just broken up – and, to top it all, he wrote an incredible work that he did with Irakere to open the night: Concierto Andino. Everything was a bit dizzying but also very motivating.”

New visit to Chile

From there, the musician has strengthened a frequent live relationship with Chile, extended in the most diverse presentations, acts and recitals even in regions. A bond that will be revived with two shows set for the second semester: they will be on Monday, September 29 and Wednesday, October 1, at the Movistar Arena. It is his return to the capital after 2018, when he played three dates at the same venue in Parque O’Higgins.

“I will be accompanied by extraordinary musicians, they are friends with whom I have had fun for years. That is always a guarantee,” he says regarding his presentations in the capital, where he will show part of his latest album, Quería saber (2024).

-What is the importance of Chile in your career?

To begin with, it was the first Latin American country I visited. In September 1972, Gladys Marín, whom I met through Isabel Parra, invited Noel Nicola, Pablo Milanés and me to a Jota congress. At the same time, an international exhibition was being held in Santiago and I remember recording a group of songs for the Cuban venue at that event. Every night we went to the Peña de los Parra, where we had an idea of how broad the movement of the song was at that time. In those days we went to Valparaíso with Víctor Jara, to sing at the University, but I stayed sleeping in the car because I had a sore throat. I also remember that President Allende received us at La Moneda. I was close to him on three occasions.

-You have returned a couple of times to some specific events at the National Stadium in Santiago. But would you have liked to ever return for a solo show, as you did in 1990? Did that opportunity come about?

From 1990 until a few years ago I made a few solo presentations in several Chilean stadiums, always very well attended, but, as far as I know, I did not have the opportunity to do it again at the National Stadium.

-In April of last year, the Chilean band Los Bunkers gave their first show at the National Stadium in Santiago. They made a complete album performing your songs in Música Libre (2010). Was there any arrangement for you to have participated in that show?

Yes. They were kind enough to invite me and I confess that I would have liked to accompany them very much. Unfortunately, it was not possible. Coincidentally, a few days ago I saw a video of them performing El necio (The Fool) in a concert. Without a doubt, they made a very powerful version.

Retreat?

-Last year, you also gave an interview to Culto and said that you did not plan to promote your latest album, Quería saber, through a tour. Now you are coming to Chile in the second half of the year presenting this album live. What made you change your mind?

The concerts are not intended to be the presentation of Quería saber (I wanted to know). It’s even likely that I’ll release another record before the tour. Of course I’ll do some songs from my latest works. There will also be others that I have in my hands, in addition to some inevitable ones that are usually in all concerts.

-What motivates you the most today to go on tour?

I’m always motivated to make music – or dream that I make it. I was extremely lucky to be able to dedicate myself to something fun, which is a pleasure to share.

-Have you never tired of performing live?

Initially I never thought about singing my songs. I just wanted to write for others to interpret. But a great Cuban musician, named Mario Romeu, listened to me, orchestrated a couple of songs and introduced me on television. I ended up even hosting a programme. In your 20s, these things can be very stimulating. Then, over time, I went through stages of tiredness several times; but a good rest can bring back the desire. At least until now.

-How long do you see yourself publishing albums and performing concerts?

I may spend more time releasing albums than doing concerts.

-Is the word “retirement” part of your immediate lexicon?

Officially, by the laws of my country, I retired when I turned 60. I had a party and everything. Although since then I have worked as much or more than before.

-If in the rest of your career you were given the option of collaborating with an artist, who would you choose?

If you knew… Last year I had to publish a text declaring that I was not going to do any more collaborations. It is that requests are constantly coming in; so many that I have come to collaborate with hundreds of other people’s projects. But the years have made me think that I must dedicate myself to the many things that I have left half done; sometimes songs; other times entire albums started and abandoned by touring. Not to mention what I keep coming up with, that does deserve attention.

-Are you worried about what is written about you in the future, the legacy that your music will leave, how your work will be analysed by the generations that follow you?

I am not concerned about what is written about me in the future – not even in the present. I have no illusions about it. I am aware that I am not Anglo-Saxon – the most widespread culture in the world’s media, due to its economic power. I don’t owe anything to the transnationals or the powerful record labels. To make matters worse, I am from a marginalized country persecuted for being rebellious. I have simply done what I could within the wonderful worlds of music and words, and I have enjoyed it. In Cuba they say: “A mi, que me quiten lo bailao”.

Dogmas and urban music

-Do you have any opinion of current music? Today the so-called “urban music” and artists like Bad Bunny reign in Spanish-language music.

I have heard different expressions of the so-called “urban music”. I know hip hop, rap, trap, reggaeton. Now, in Cuba, there is a variant of this music that they call reparto, or reparterismo. They are expressions that seem to come from humble sectors and I suppose that, in part, they are the result of new technologies, music programs that work even on phones.

-There is a very interesting song on your latest album: Para no botar el sofá. There you say: “I don’t want a hug with limits, nor a kiss as an obligation, I don’t want vices and dogmas planted in my heart. I saw them truncate publications, intelligent people, and disqualify songs for being different.” What did you try to portray in this composition?

I’ve never liked to explain songs. I did that one of the times we talked on my blog about our reality, from different points of view. I’m just talking about how I prefer free will, not impositions (a difficult thing in this world).

-Did you consider yourself a dogmatic person at some point?

Dogmatism, in the best cases, is nothing more than ignorance and stubbornness. For my part, I have always had the habit of asking myself questions, and even of not settling for the first thing that comes to me. I think it shows in my songs. From a young age I identified with the word ‘Apprentice’.

-You say “I saw them disqualify songs for being different” on this song. I understand that you were referring to the mistrust generated by the appearance of Cuban nueva trova singers at the time of the Revolution. Why do you think this was generated? What kind of distrust did they arouse?

In the first place, our songs began to use many words that were not usual in what was heard at the time. Some began to say that we were “weird”, others to say that we were “surrealists”, others that we were “elitists”, others that we were “foreigners” and some, too, dared to use the word “counterrevolutionaries”. It is something that usually happens when something different comes up, not seen, not heard before. It is the unconditional attachment to the known, because it is “safe”, and the rejection of the new, to the unknown, because it is “transgressive”. Something that has happened many times in the history of the world, in all latitudes.

-Do you think that this generation of singer-songwriters is unrepeatable?

Like all generations, mine is the result of a becoming, a history and specific circumstances; and of course also the result of the development of technology and communications. In my time recording a song was almost impossible. Now anyone does it with a phone, and it is even filmed and projected into the ether. Very different.

The situation in Cuba

In a recent post on your blog Segunda Cita (Second Date), you said regarding Cuba: “Different signs suggest that a kind of gradual disappearance of the sense of national dignity is occurring. I feel it in everyday citizen events.” What do you mean? Do you think the sense of national dignity is disappearing in your country?

Cuba has been the victim of a genocidal blockade – as Gabriel García Márquez described it – for more than 60 years. This has forced us to spend enormous resources resisting and trying to circumvent it. To make matters worse, our enemies have us on a list of terrorist countries, which further limits our trade and relations with the world. Although I am convinced that the blockade has generated our greatest difficulties, I am not one of those who blames it for everything; I am aware that in the desperate struggle for survival, mistakes have also been made, political and economic dogmatisms. This set of factors has caused not only material but also spiritual wear and tear, which is reflected in frivolity and citizen apathy with which we deal daily. It is not the first time that I say that one day a scientific paper will be written on the profound damage that this situation of constant and growing hatred and harassment has done to the Cuban people. The threatening statements of the head of the Southern Command of the powerful U.S. army and those of other imperial officials have just demonstrated their validity.

Are you concerned about the rise of the far right and totalitarian ideas that have been seen in different countries in recent years?

I am concerned about many things. In the first place, there is so much greed, selfishness, brutality; so much impiety, so much crime and genocide go unpunished. It is unbearable to see what they do to the Palestinian people on a daily basis, in full view of the world. I am deeply concerned about the example, the terrible lesson that all this is leaving in the new generations. I am also concerned that there are dogmas that distort noble ideas. Sometimes it seems that we are not capable of learning. José Martí, the Apostle of Cuba, said that he had faith in human improvement. These are times when it is not easy to maintain that faith. But we have to overcome and continue.

Original interview published by CubaDebate and LaTercera

You must be logged in to post a comment.